Despite Cézanne’s insistence that the world, with all its strangeness, only becomes present, comprehensible and recognisable in images, the onset of modernity initiated a disappearance of nature and landscape in the course of a rational logic of progress. Matisse, Munch or Klee were already only able to preserve them in pictorial form.

In its mere facticity, the fragmented succession of immaterial data and countless, disjointed moments do not create a world. In such an inescapable and incoherent present, without history and thus also without a future, it becomes palpable how fragile and disoriented our being-in-the-world, whether individually or communally, has become.

An image, which simply showed what is there, today would be an act of resistance. By allowing the world to be present again and empathically asking what might constitute being-there, it would be independent yet simultaneously at the height of the times.

With 30 individual views on landscape and nature, the group exhibition das gelbe Licht 6 Uhr nachmittags maps out the hazy mosaic of a frail present: whether as a melancholic reminiscence of man-made devastations, a stoic contemplation of the fragile fabric of everyday life or a daring invention of an uncertain future yet to come.

And all of this largely without people. Yet, as the exhibition title, a line of poetry by the late Rolf Dieter Brinkmann, suggests, we, looking and empathising, are ourselves the missing human reference. For the question of how we want to fit into the world arises again and again.

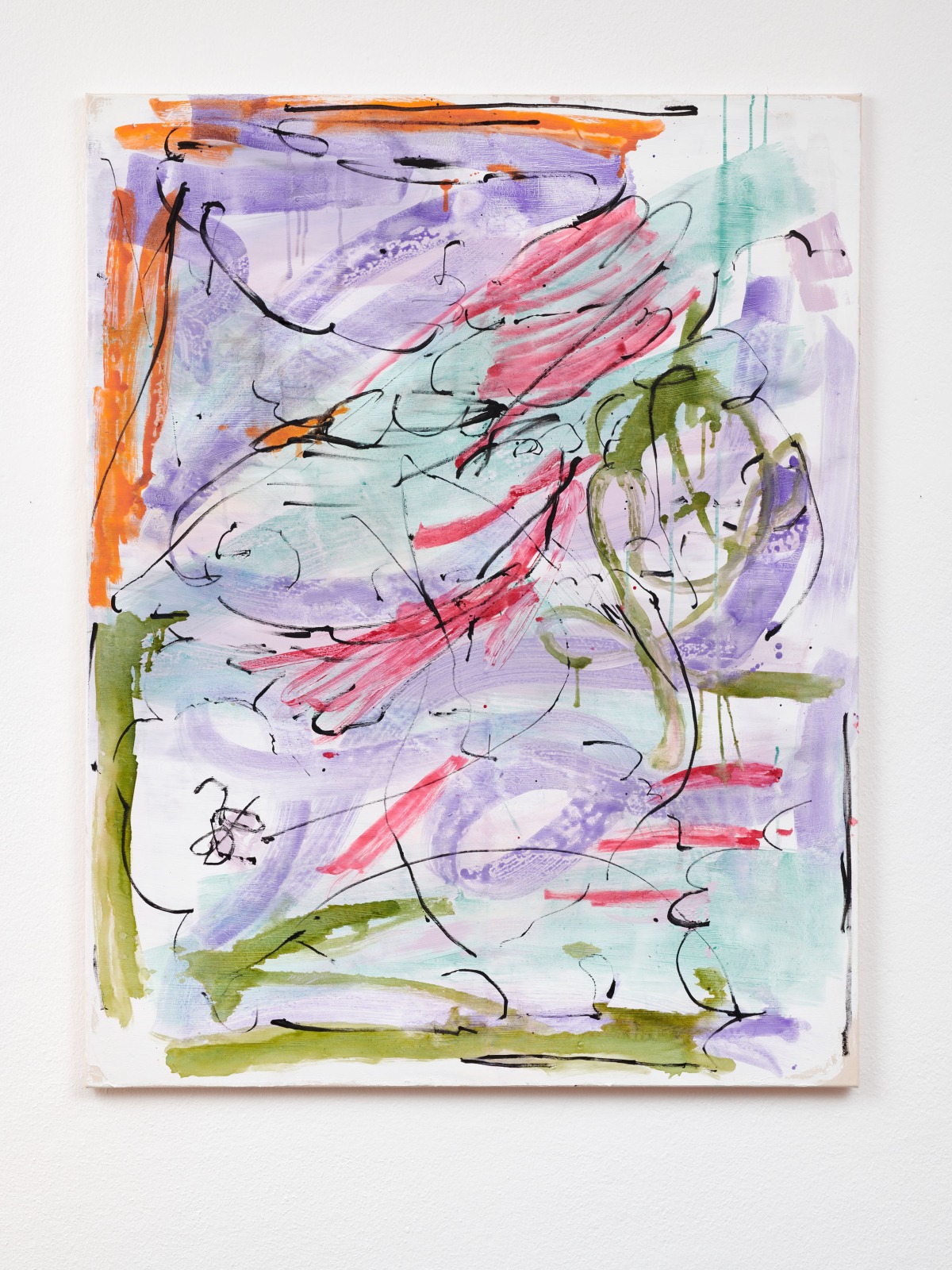

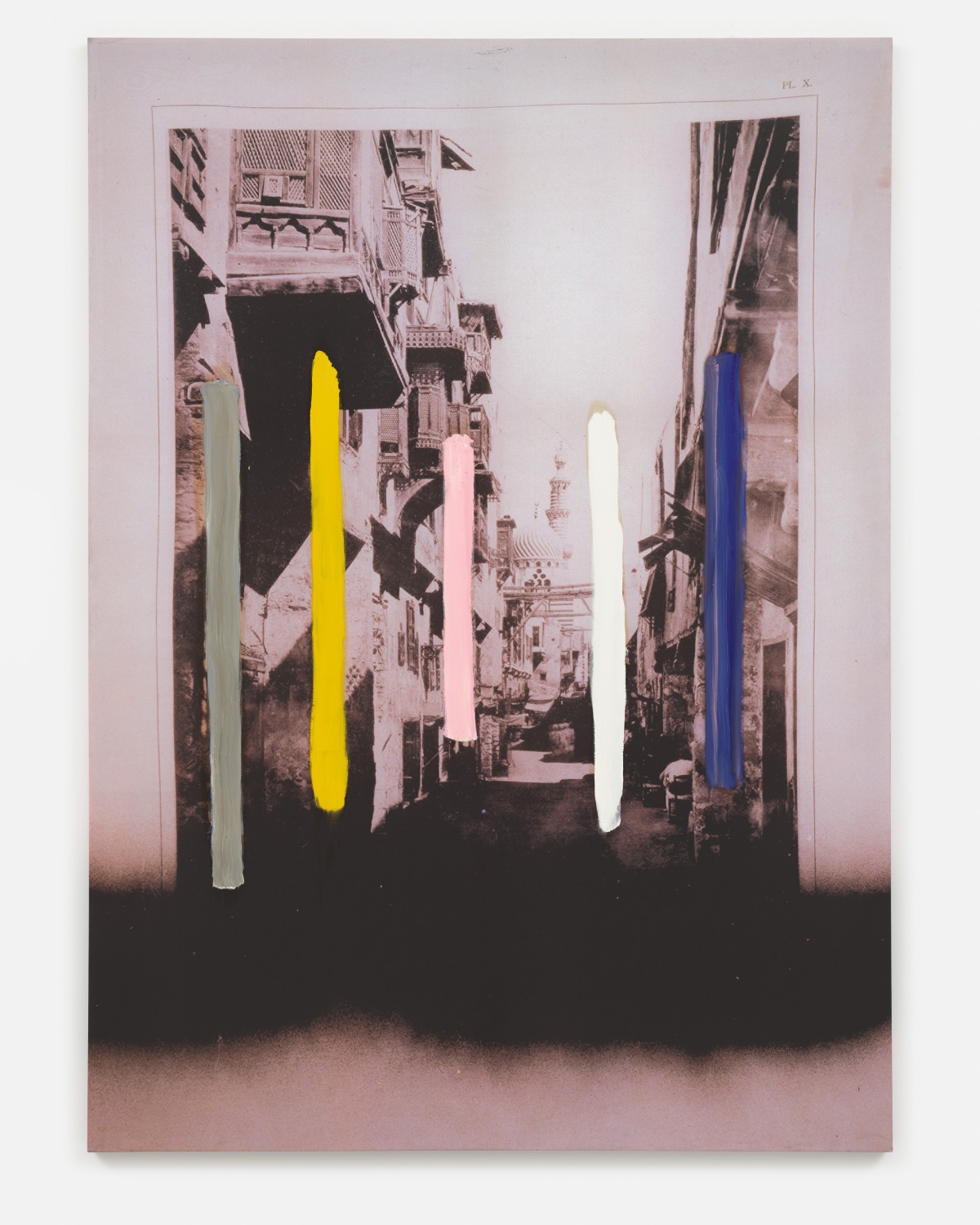

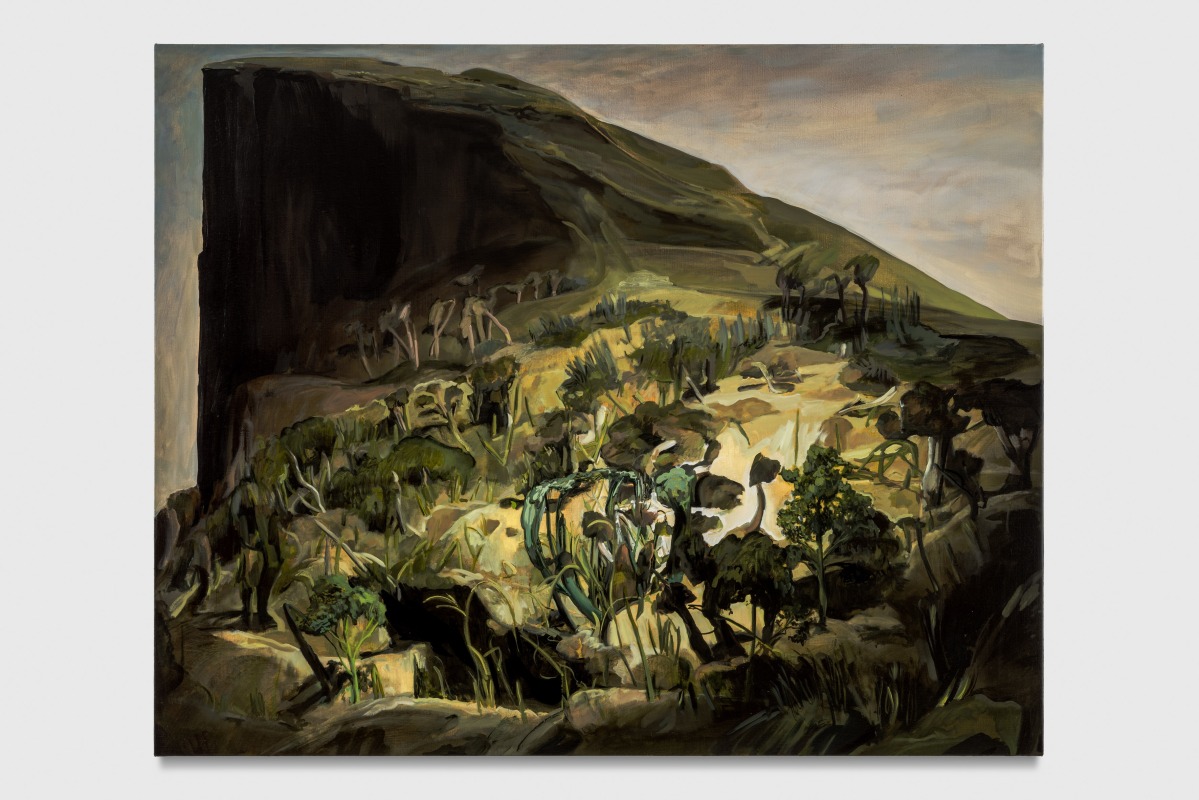

Along trembling landlines like Sean Scully (*1945), who traces the enormous geological shifts in his pictorial tectonics. Like Emma Webster (*1989), who abruptly brings the world and the image to an end amidst barren cliffs and lush vegetation. Like Glenn Brown’s (*1966) grotesquely confident symbiosis of man and plant. Or Julian Schnabel’s (*1951) painterly archaeology of historic cultural sites and images. Hedwig Eberle (*1977) captures intangible sensations of bodies and landscapes in her paintings, blurring the boundaries of figure and formless colour.

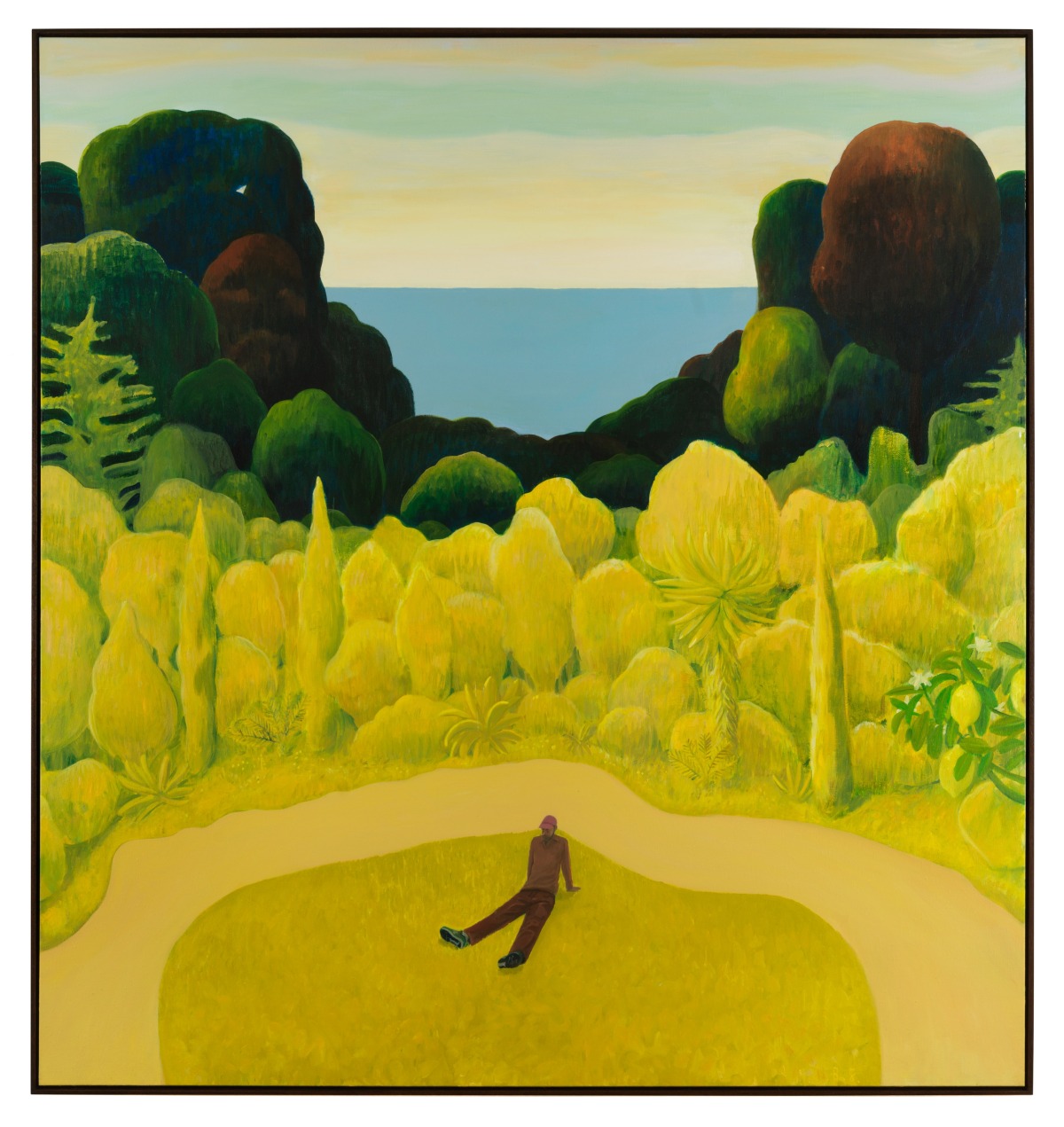

Ben Sledsens’ (*1991) paintings seem to have fallen out of time, like dreamlike sceneries of forests, coasts and meadows, protective realms, albeit subliminally foreboding. Katharina Grosse’s (*1961) paintings become natural phenomena in themselves, painted with weaves of seaweed or kelp. Grace Weaver’s (*1989) interiors no longer seem to have a world; windowless, their only connection to the outside is a computer screen, which only illuminates a blank void.

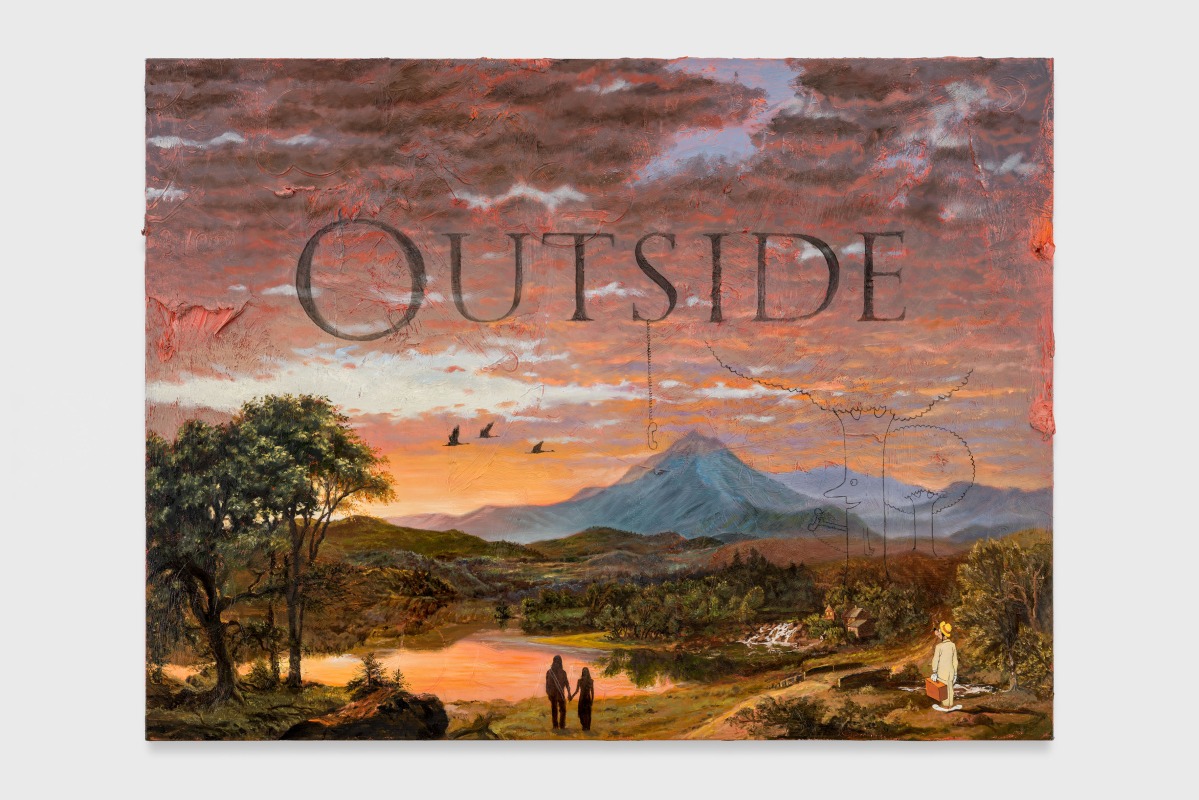

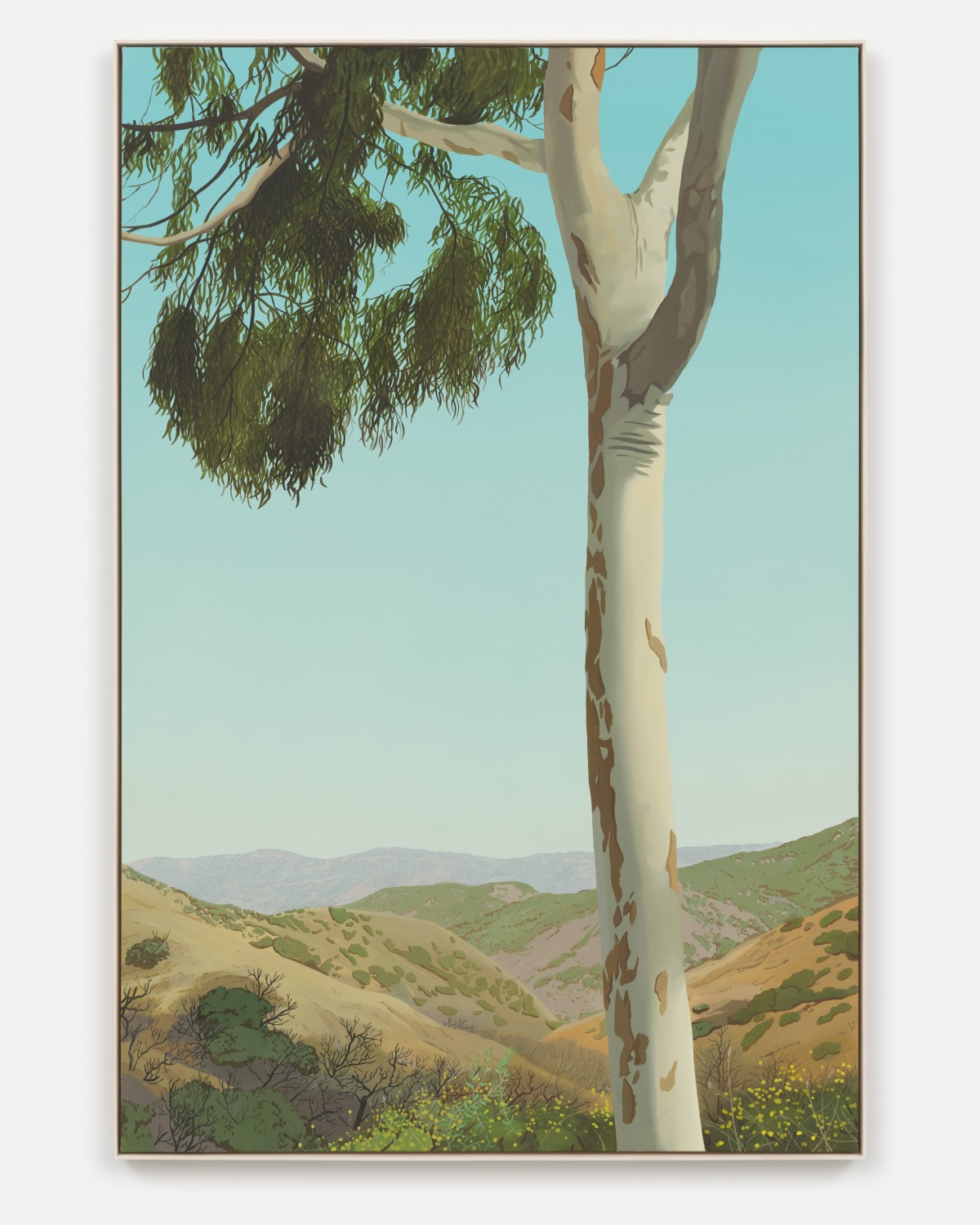

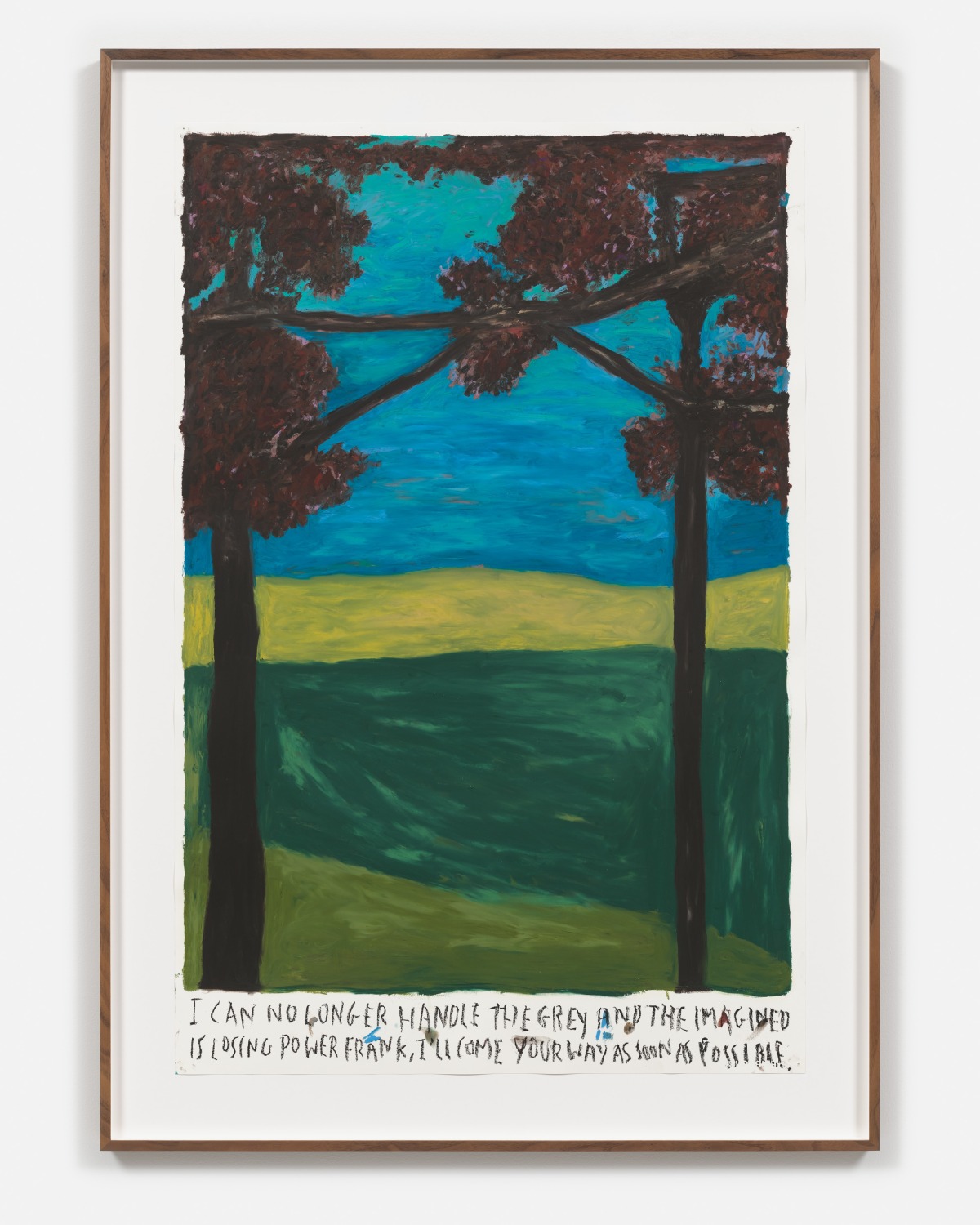

For Friedrich Kunath (*1974), the great “outside” no longer serves as material for romantic ballads, but can only be endured with skeptical amazement. Time seems virtually halted in Jake Longstreth’s (*1977) muted Californian landscape, while Rinus Van de Velde (*1983) reveals an unknown chromaticity through the liberating view of trees, fields, mountains and the sky. Melike Kara’s (*1985) abstractly interwoven paintings continue to spin the repressed Kurdish history and inquire into the challenges of a new community and Mònica Subidé’s (*1974) female figure embodies the changing life cycles of becoming and passing.

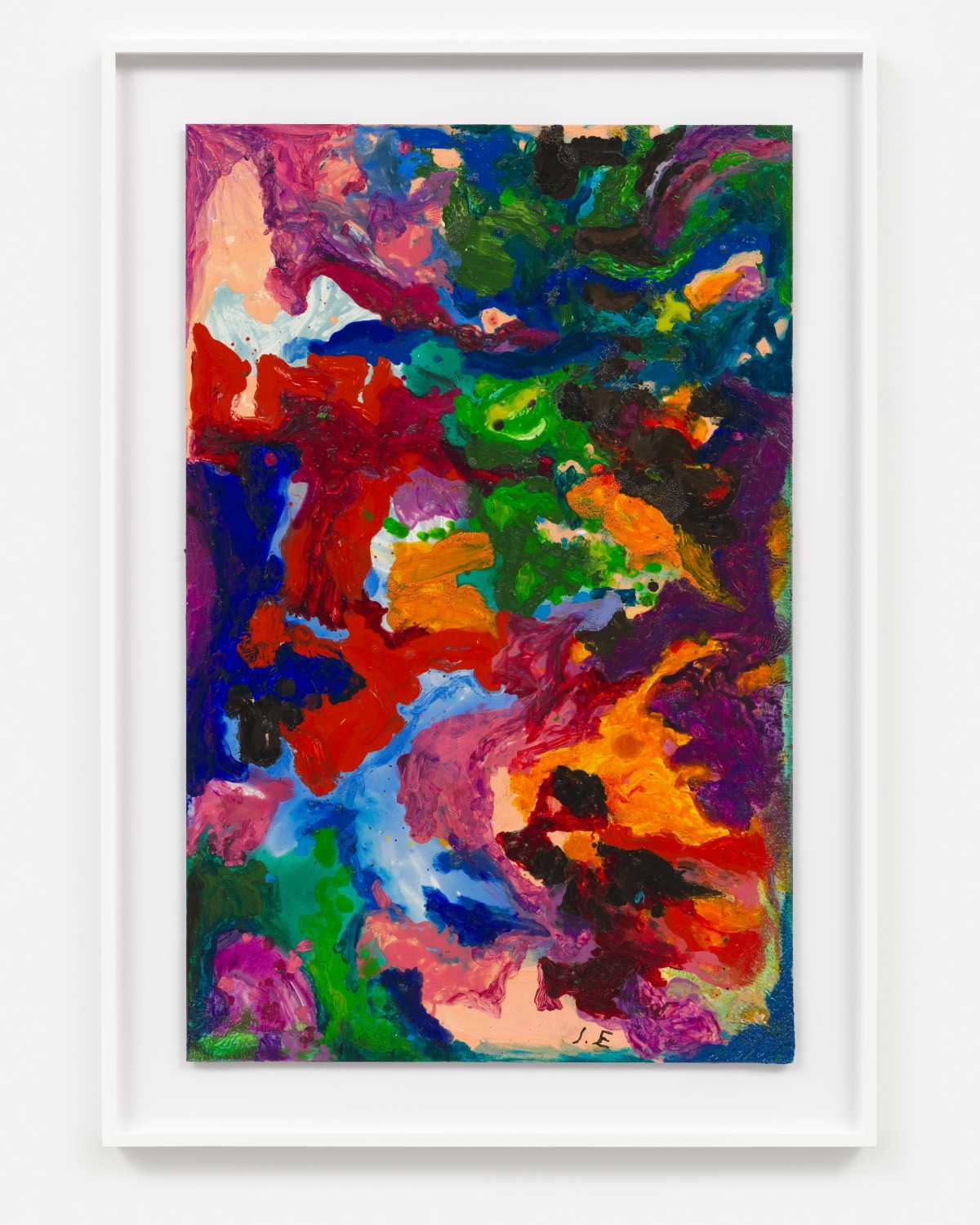

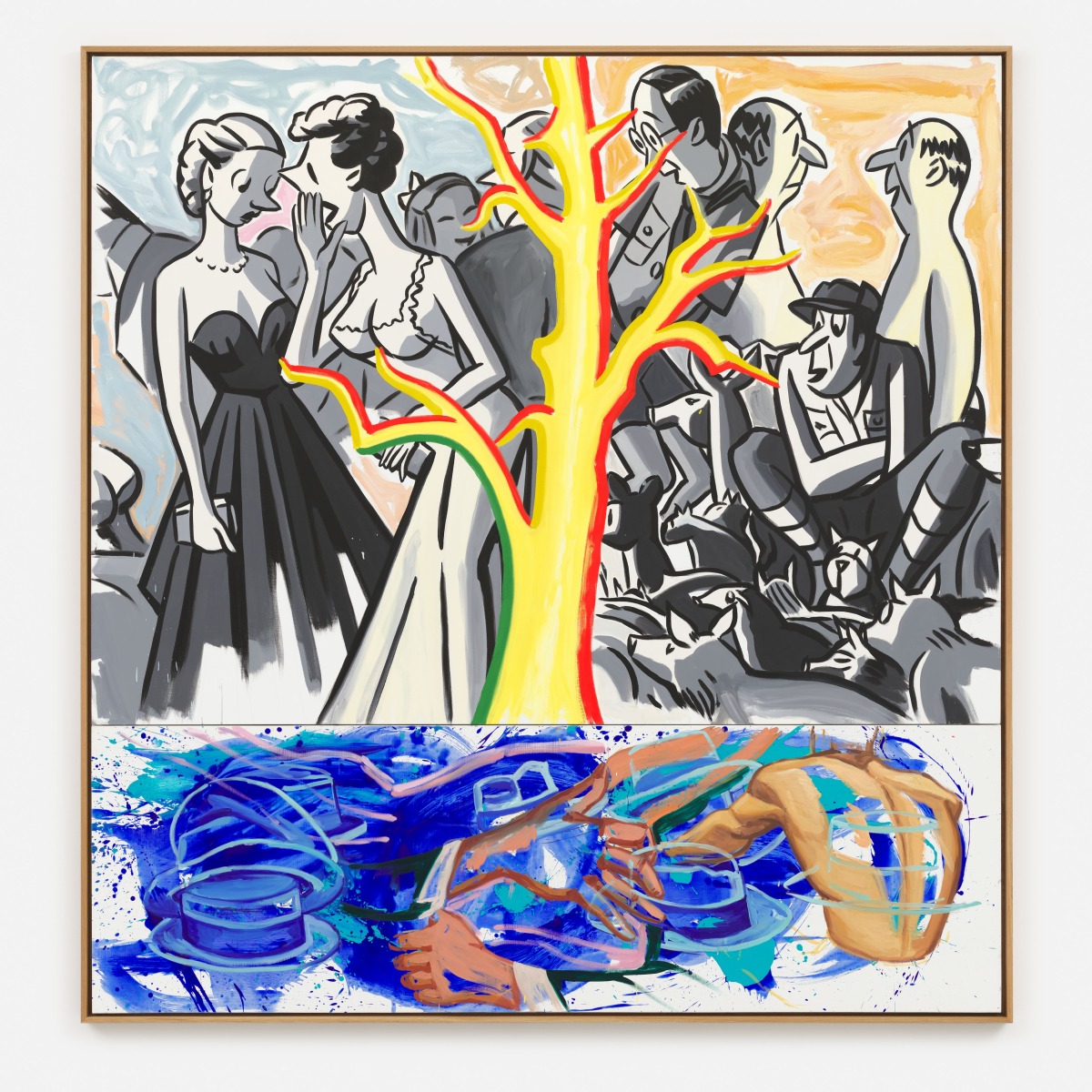

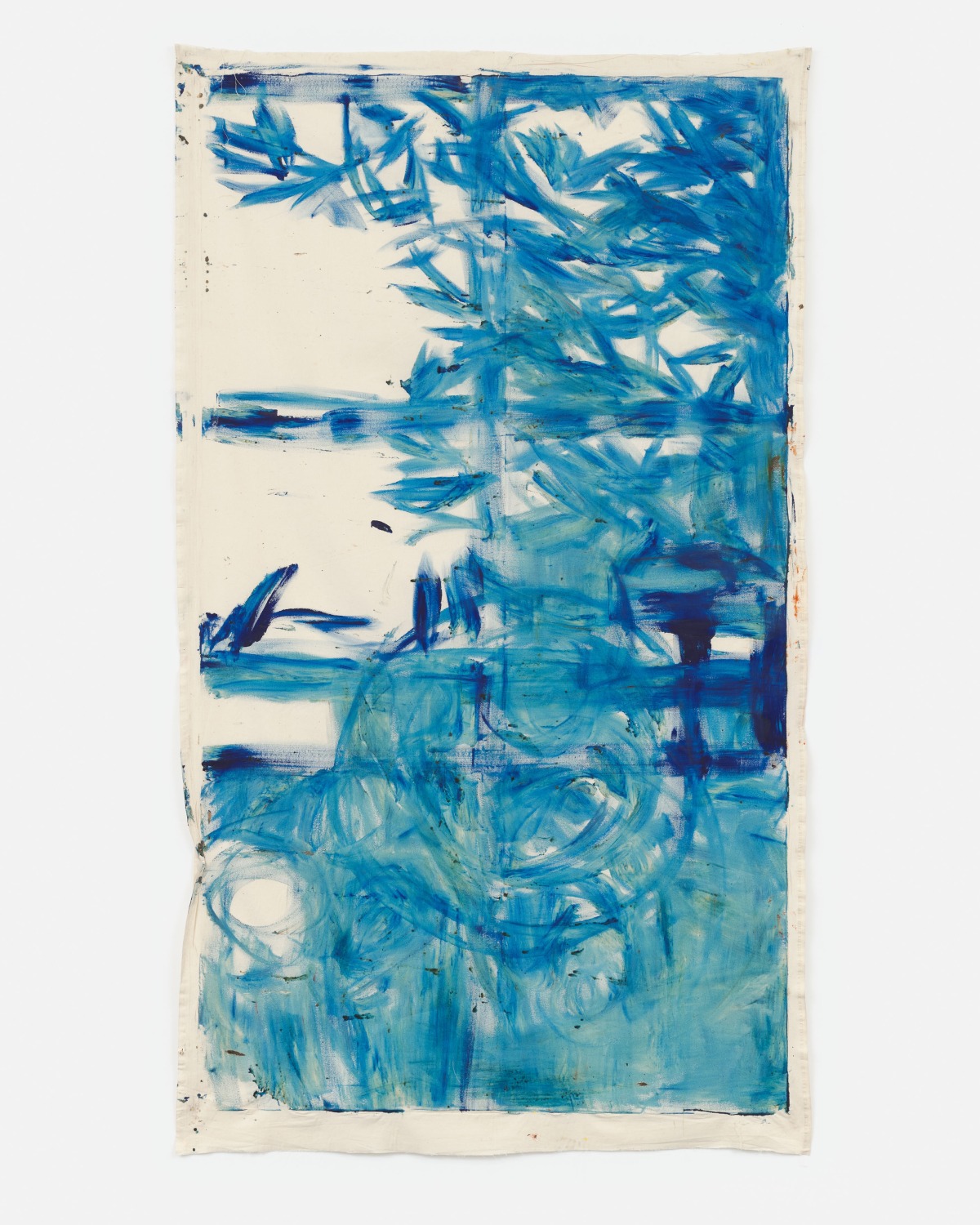

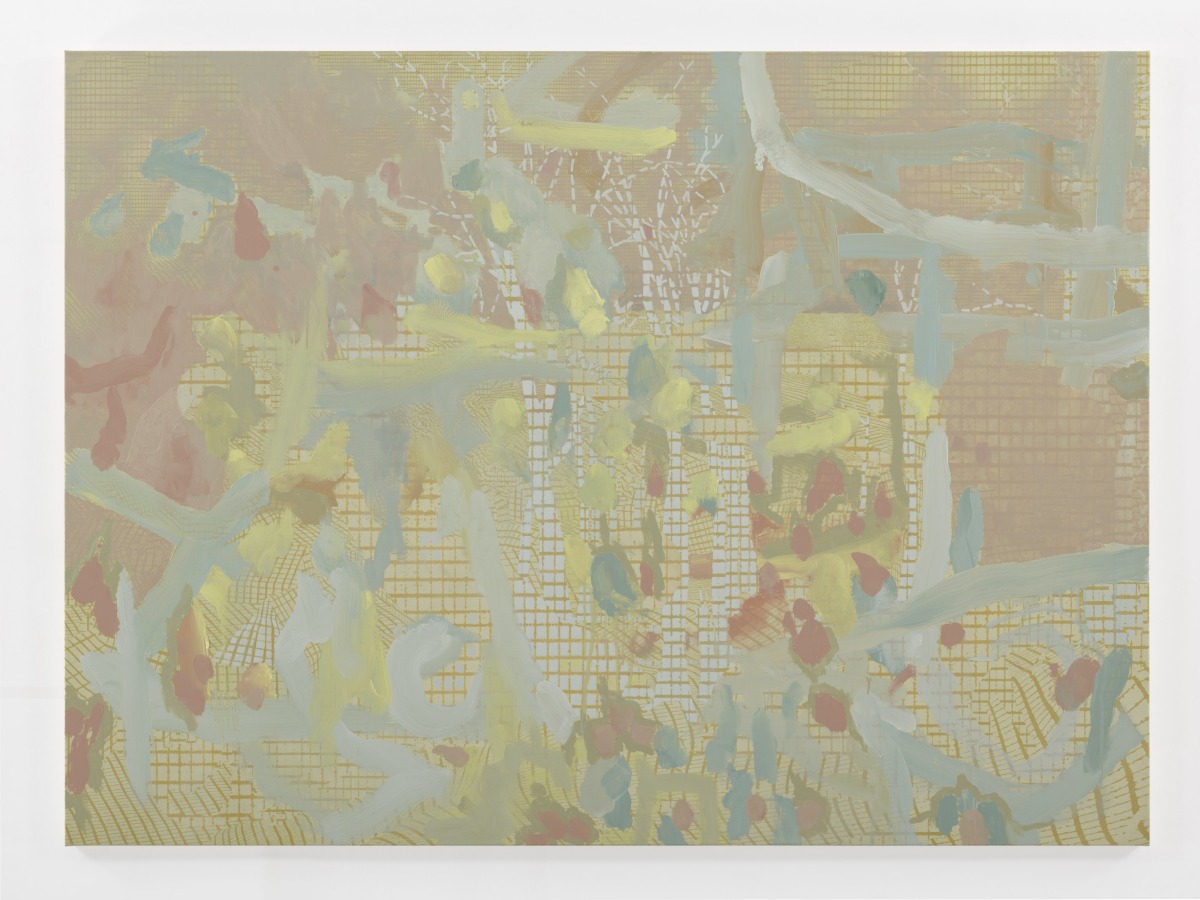

In front of an endless ocean or sky, Darren Almond (*1971) makes the number 0 appear: Nature as a symbolic void, a projection. In a corroding confrontation of antiquated natural history and the latest social gossip, David Salle (*1952) lays bare how fragile the entire present has become. Shapeless colour, painted into clouds, forests, and grasslands, is what Tursic & Mille (*1974) bring to bear against the endless clichés of what is supposed to be landscape. Beth Letain (*1979) excavates buried impressions and occurrences in rhythmically pulsating, geometric constellations, which might just be colour, or perhaps trees. Toby Ziegler (*1972) transforms given situations or sites into flat topological spaces, which he, in turn, transfers to canvas, thereby reattributing depth and dimension to digital alienation by painting. Between excess and ecstasy, Ida Ekblad (*1980) brings forth a world in dissolution, stroboscopically fragmented, deliquescent, but sunlit. Sarah Crowner’s (*1974) rhythmic permutations of colour and form, however, appear like swaying foliage seen against the light. Rock, water, vegetation, wind – Liliane Tomasko (*1967) condenses the opposing forces of nature into a suspenseful whole, the image becoming a month’s worth of experiences.

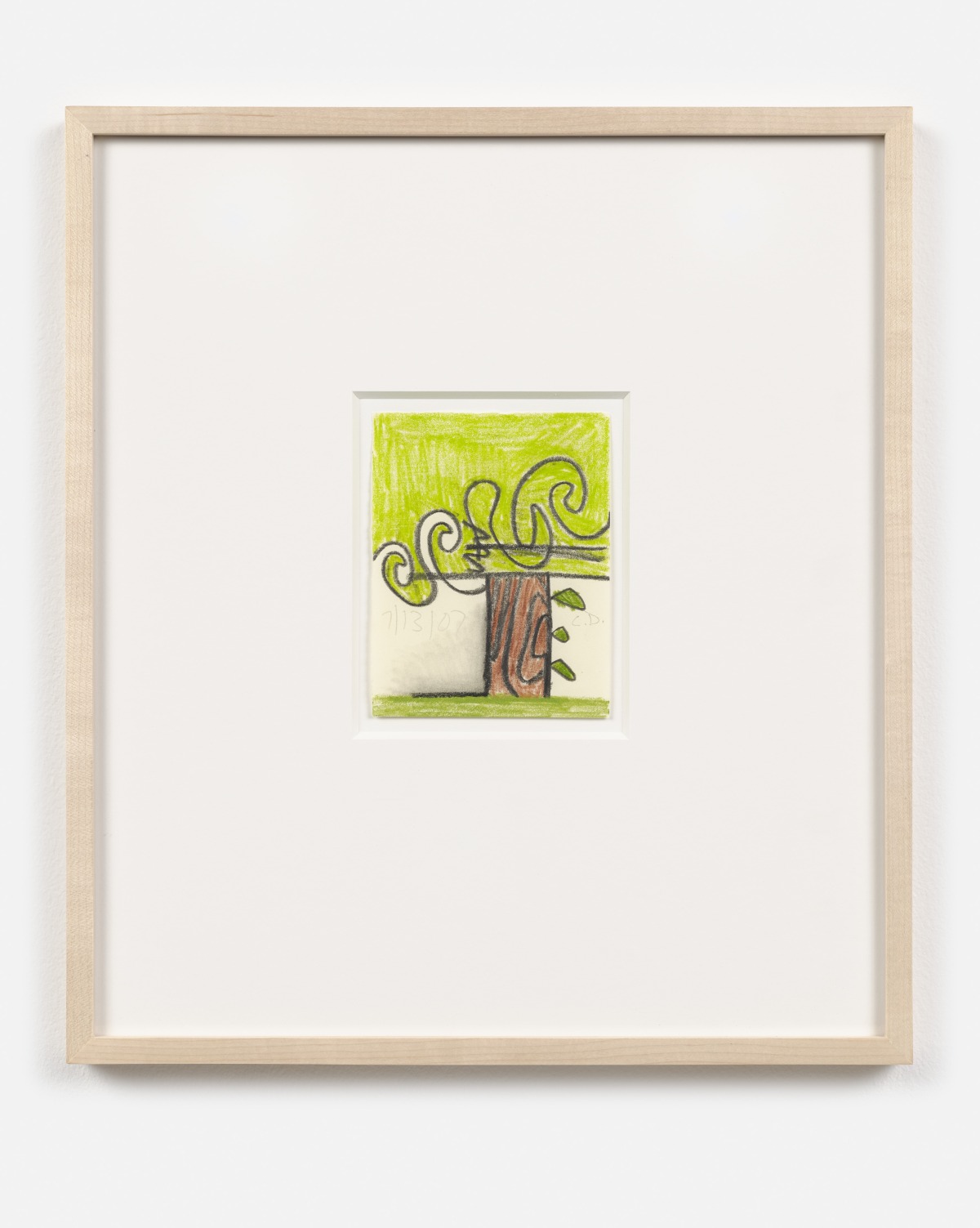

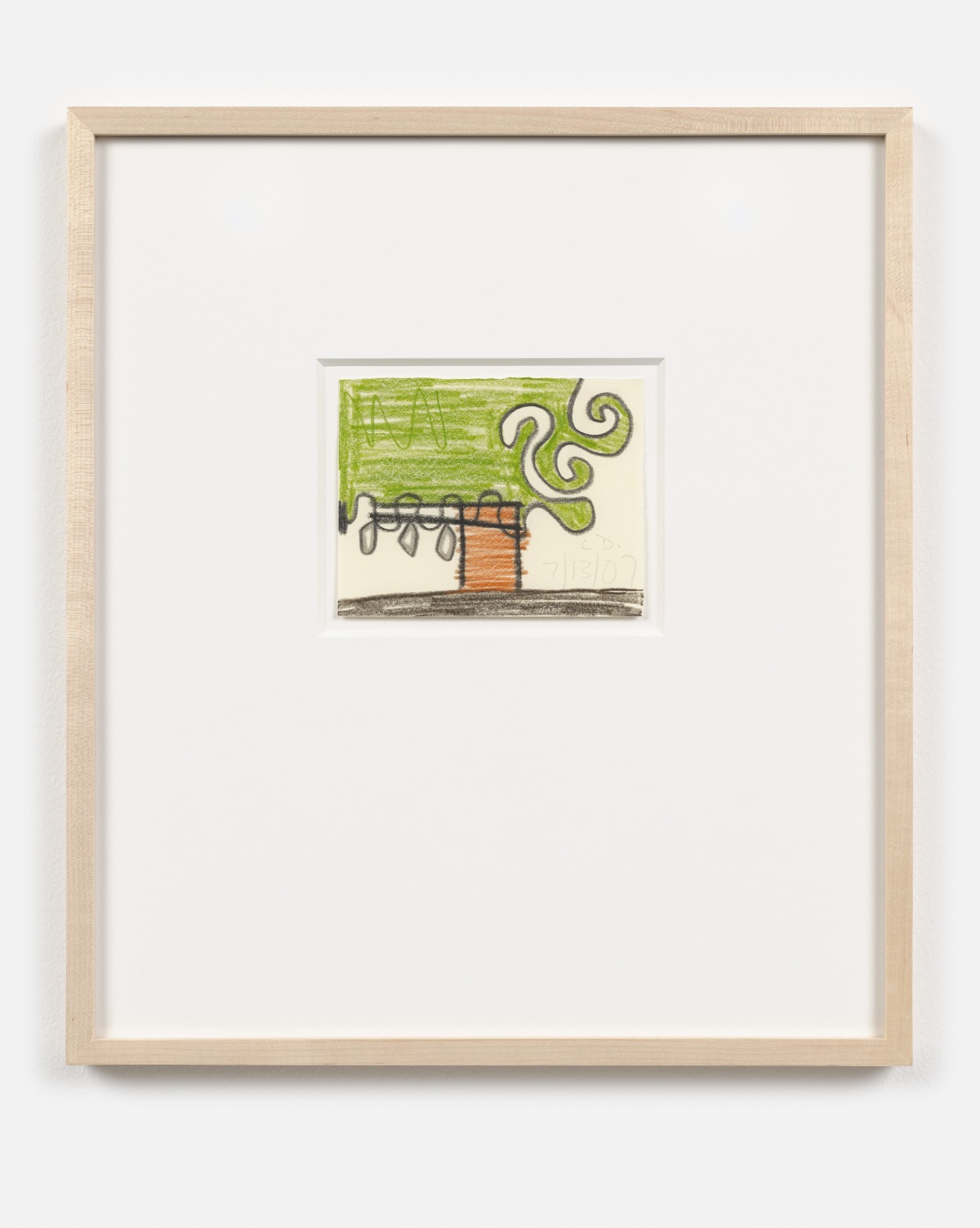

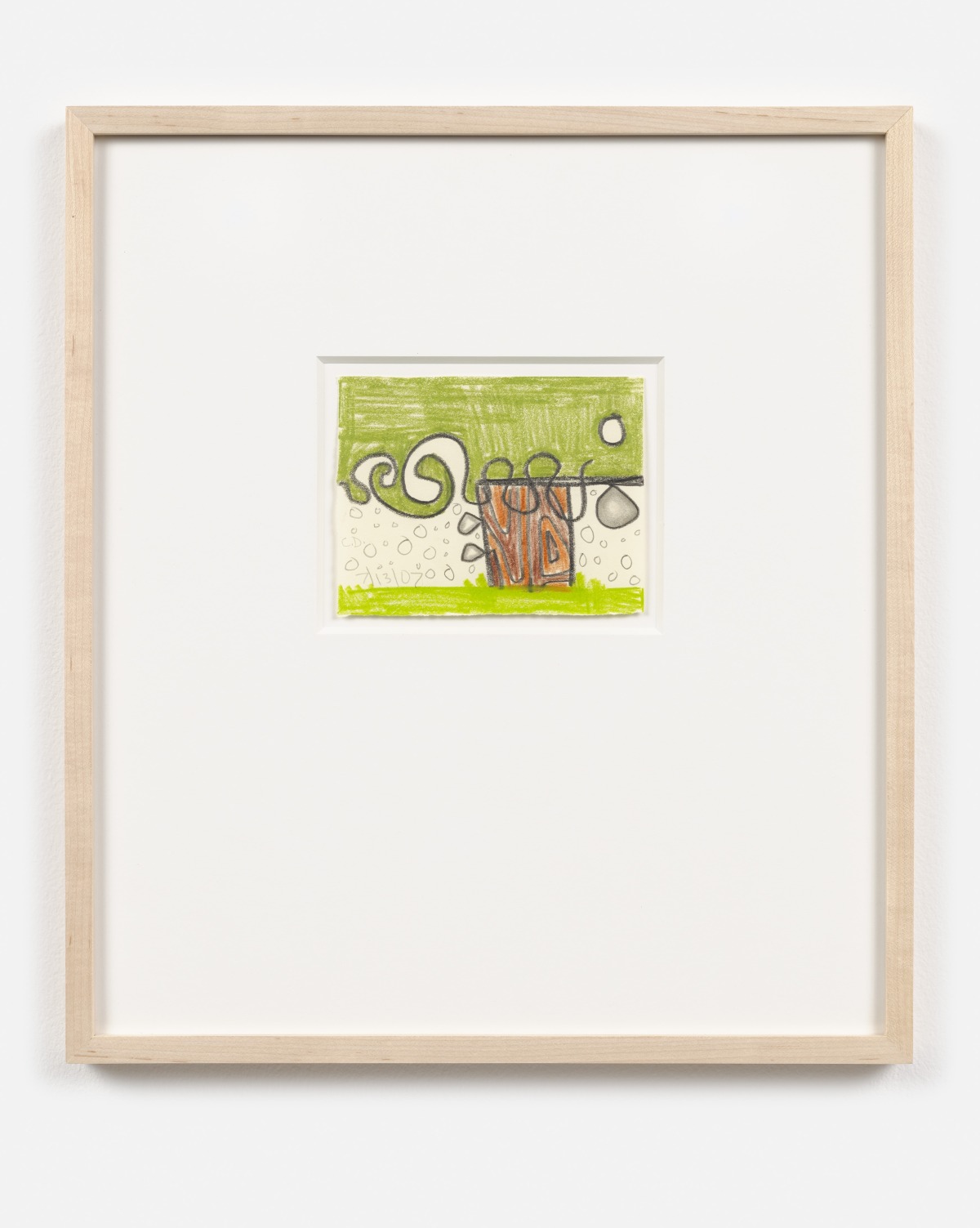

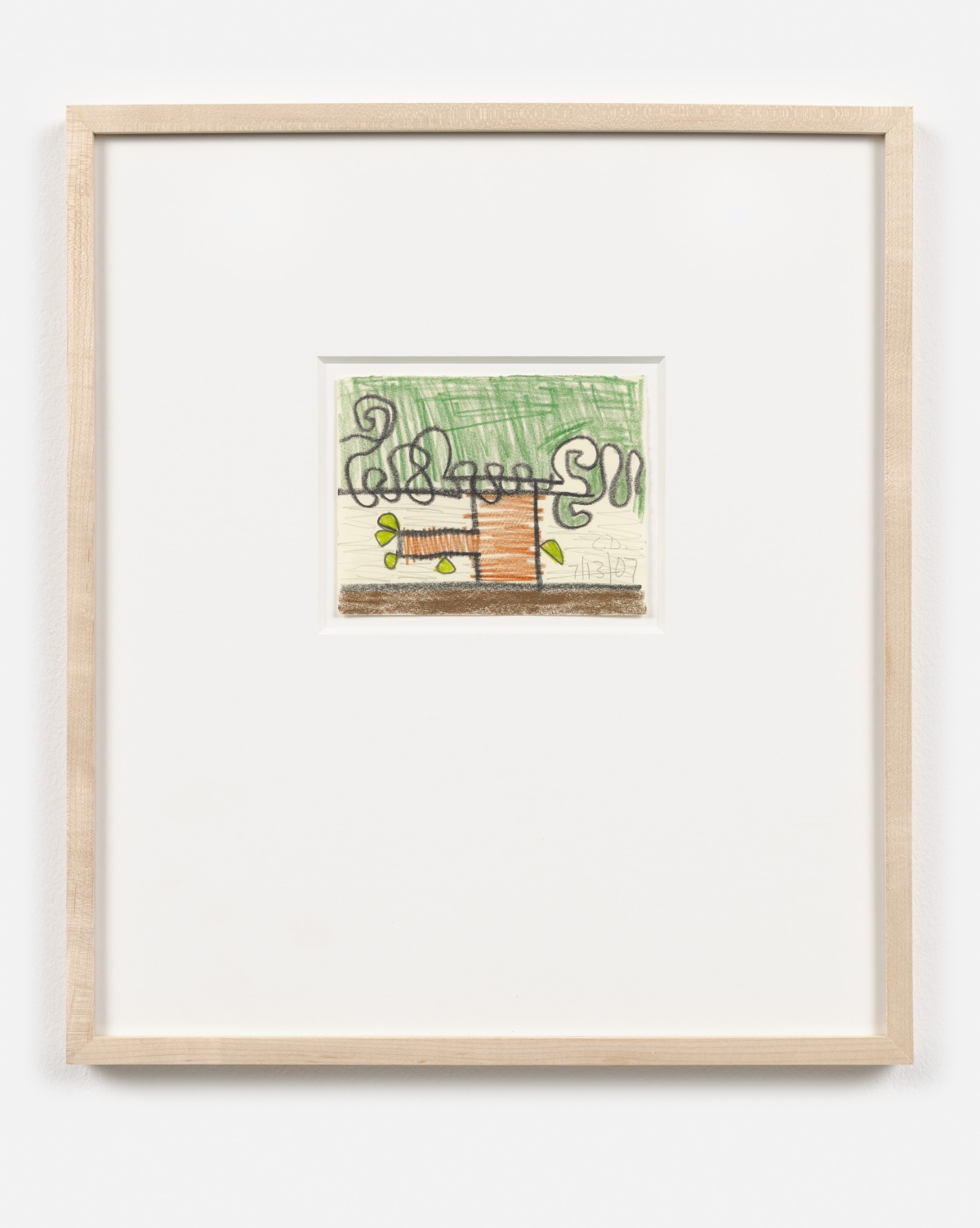

Alex Israel (*1982) envisions a place of longing like the Malibu Pier as a mindscape, cool and yet indulgent, familiar and yet always out of reach. On reflecting water, a solitary floating raft becomes a symbol of human existence for Alex Katz (*1927). In contrast, Carroll Dunham (*1949) immerses himself in sparse tree studies, at times sweeping and ornamentally proliferating, at other times block-like and austere. David Schutter (*1974) meticulously recreates the life of the near forgotten American landscape painter Ralph Albert Blakelock, an absurdly abysmal dance of colourful ghosts.

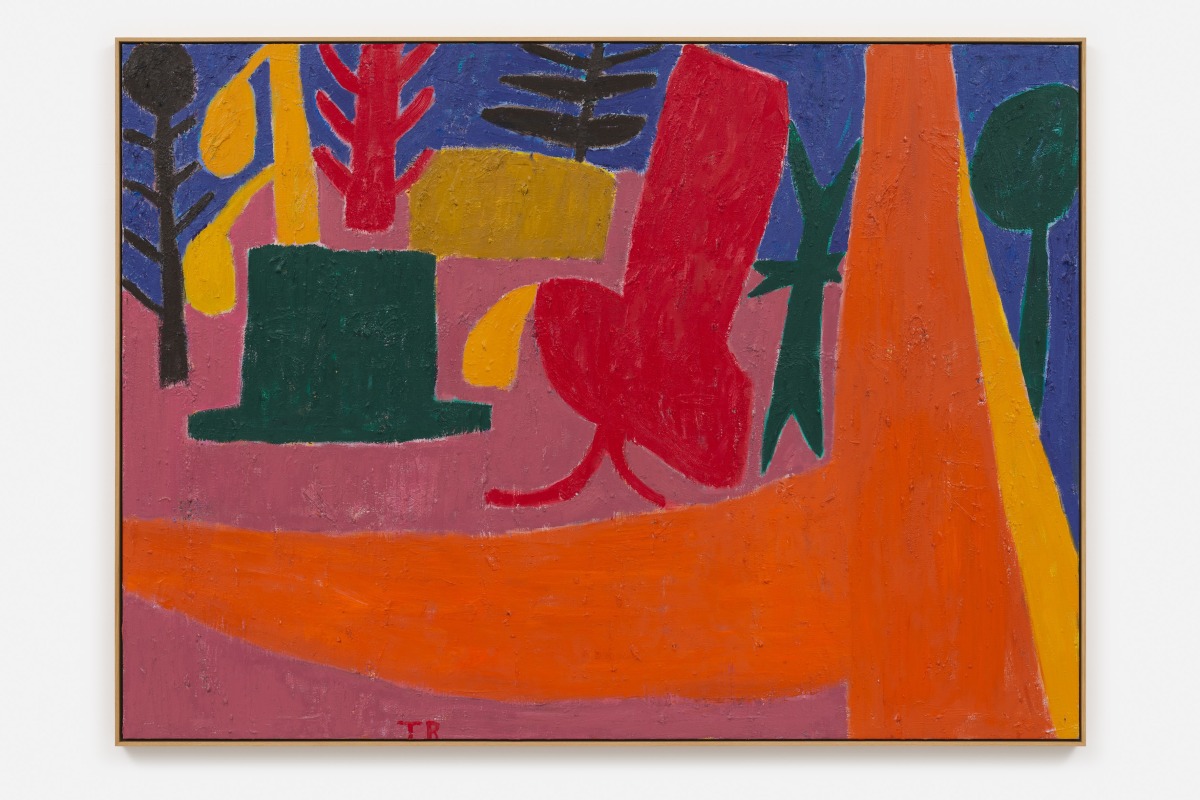

Günther Förg (1952—2013) inscribes history into his paintings; the reddish-brown and reddish-red earth colours bear their origins in their names like bloodlines and at the same time call up his own biography and very first paintings. Vivian Suter (*1949) exposes her paintings to the forces of nature, so that they themselves take on natural features; weather and body, colour and gesture become one. Georg Baselitz (*1938) recalls his own origins by means of a forest, a childhood motif, which had already been brought into the picture fifty years earlier and is now used anew as a shadowy reassurance of the present. A sense of space is often present in André Butzer’s (*1973) paintings, as experienced places, in the built, planar topography of his images or in “Schlesien” (Silesia) as a memory of a landscape’s lost history and culture. Tal R (*1967) undertakes an immediate positioning instead, the landscape is wide with trees, tree stumps, a top hat and bird, the colour is gnarled or thick like clay and there is a path through it, up and then left – but where to?

Landscape

Rolf Dieter Brinkmann

Westwärts 1&2 · Poems, 1975

1 sooted tree

no longer definable,

1 car wreck, shards of glass

1 stud wall, sound-absorbent

different broken shoes

in leafless undergrowth

»what are you looking for?«

1 essay, an excursion into biology

the search for caddisfly larvae, the yellow

light at 6 pm

1 pair of stones

1 warning sign »Private«

1 carted rotten sofa

1 sport plane

several fleeing animals,

the rest of a pantyhose on

a branch, aside

1 rusty bicycle frame

1 memory of

1 Zen joke

Press contact:

Galerie Max Hetzler

Honor Westmacott

honor@maxhetzler.com

Berlin: +49 30 346 497 85-0

www.facebook.com/galeriemaxhetzler

www.instagram.com/galeriemaxhetzler